Translating Research to Practice: Evidence-Based Design for Workplaces and Offices of the Future.

Guest post by University of Leeds Business School and Atkins.

The world of work has recently faced numerous challenges, following the introduction of new and alternative ways of working in response to post-pandemic working patterns and pressures to address wider changes related to contemporary work cultures. In this context, the use of evidence-based approaches is becoming increasingly prevalent as designers strive to make more informed choices that support health and improve experience.

This article discusses the importance of integrating applied research into design and evaluation processes, through the ongoing collaboration between the Atkins Building Design Research and Innovation team, and the University of Leeds Business School.

What is Evidence-based Design, and what does it mean for us?

Evidence-based design is described by The Centre for Health Design (2022) as the “process of basing decisions about the built environment on credible research to achieve the best possible outcomes”. This approach is often associated with healthcare facility design and can be traced back to Roger Ulrich’s (1984) seminal research, and one of the most cited papers in architectural psychology, investigating the effect of window views on patient recovery. In recent years, the approach has continued to gain popularity for the design of other building types, as it provides a way to evidence design decisions through a growing body of research on the impacts of physical environments on stress, productivity, comfort, and more.

An evidence-based approach, enhanced by further collaboration with academic partners, can improve the way design options are evaluated, inform design decisions, and improve engagement with stakeholders; aspects that are central to Atkins’ approach to design.

In the context of workplace design, the pandemic and subsequent lockdowns, affected the way people work, how offices are occupied, and the overall future of commercial real estate. In turn, this multifaceted shift created uncertainties and complexities around the spatial, technological, and management requirements of contemporary, post-pandemic offices. As clients face the challenge of adapting their workspaces in response to this shift towards hybrid and alternative ways of working, they reconsider the utilisation of their premises, a process that requires structured information that can highlight workforce priorities and challenges as a basis for decision-making. Adopting an evidence-based approach provides support in addressing these uncertainties, particularly around employees’ return to work, by utilising a range of evidence from both individual organisations, and original academic research on the response of the wider corporate world.

Adapting Offices for the Future of Work

An important element of an evidence-based approach is to ensure the most relevant and recent research is incorporated into the decision-making process. As a result, academic collaborations and partnerships can play an important role in this.

In 2021 the University of Leeds launched a significant research project, ‘Adapting Offices for the Future of Work’ to explore this challenge, funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) as part of UK Research and Innovation’s (UKRI) rapid response to Covid-19. It is undertaken by a multi-disciplinary team from the University of Leeds, with backgrounds in management and organisational psychology, workplace design, architectural engineering, and information systems. Collaborating with several public and private sector organisations, including Atkins (member of SNC-Lavalin), this research investigates how workplaces have been adapted since the emergence of Covid-19 to support hybrid or new ways of working.

Adopting a Socio-Technical Systems perspective, the research aims to explore the requirements and relationships of physical design solutions, supporting technologies, behavioural changes and management practices, required to ensure office environments support productive and employee-centred working. Multiple social science research methods were utilised in the context of this research project, including organisational stakeholder interviews, diary studies, employee surveys, Social Network Analysis and industry workshops, to develop insights for partner organisations that help inform their office and hybrid strategies, with particular focus placed on understanding the impact of different work arrangements and use of space for various groups of workers (e.g. new starters, different roles).

Understanding Hybrid Working

The research highlights the popularity of hybrid working amongst employees as a permanent work arrangement, but also the importance of the physical workplace and divergent needs across employees. The representative cross-industry UK longitudinal surveys of office workers, conducted in August and December 2021, demonstrated that 48% of employees sought a hybrid work pattern, 24% wanted to work solely from an office and 28% to work exclusively from home (down from 33% in August 2021). While much of the discussion in the press focuses on how to encourage employees back to the office, this research demonstrates that the majority of staff want to spend at least part of their time back in an office, highlighting the continued impact of designing high quality and functional office spaces. The survey findings also challenge the popular assumption that the hybrid office should be primarily geared around collaboration and interaction. 29% of workers surveyed would like to use the office for low concentration solo tasks (e.g., emails, data processing), and 32% want to undertake high concentration individual tasks in the office, the type of work typically assumed to be least suited to office working under hybrid arrangements.

Decisions made by organizations regarding their hybrid working policies have significant implications for the types and amount of office space required (e.g., mandating set days in the office, allowing free choice over when and how often employees return, operating rota systems for teams). However, most organizations have yet to formalise future work arrangements. Only 34% of employees surveyed in December 2021 were aware of a formal hybrid working policy and only 18% reported that their offices had been redesigned to support hybrid working. This raises an important question, of what is meant by hybrid working.

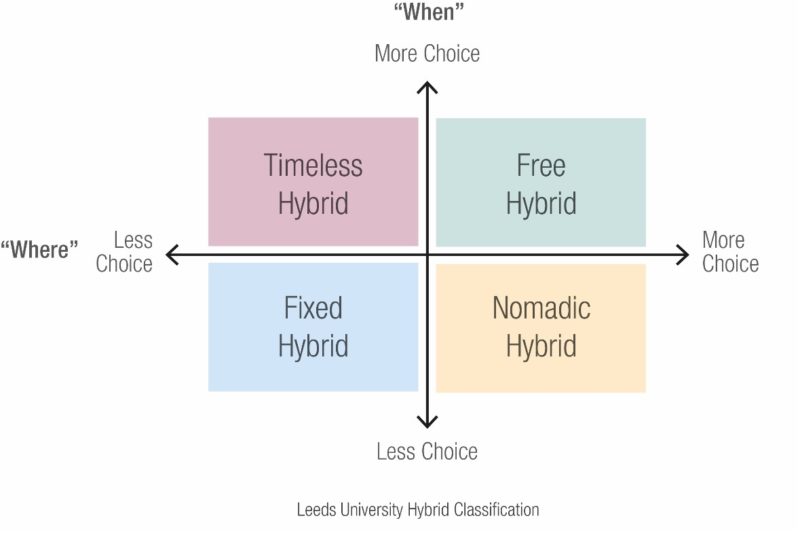

In this context, hybrid working was generally understood as a mix of office and remote working, however, this captures a myriad of alternative ways of working. As shown in the figure above, hybrid working can be classified by the degree of control organizations provide employees over where and when they work. While we may think of hybrid as providing choice and flexibility (with no formal restrictions on where or when they work, i.e. free hybrid) it can be highly prescribed and controlled (shifts and allocated office and home schedules with no employee choice over these, i.e., fixed hybrid). While organizational policies set-out what is possible in theory, employees’ demographics, life circumstances, job types, colleagues’ workplace decisions, personalities, neurodiversity needs, and networks all influence the decisions that individuals make over where and when they work. It is therefore difficult to capture these requirements, that may vary widely from one organisation to another, and design for them in a way that accurately responds to the preferences of a dynamic and diverse workforce at a time of wider change and reconsideration of priorities and approaches.

Adapting offices to support hybrid working is a truly socio-technical challenge, one where the design of the office space cannot be separated from the design of job roles, ways of working, employee rewards and performance management, or the multitude of other factors that may require redesign to deliver a functional, inclusive and attractive hybrid workplace. Evidence from the research currently being undertaken by the University of Leeds has highlighted how different office designs and configurations, technologies and hybrid working policies all influence the social interactions between team members and across organisations. This shows how decisions over hybrid policy can support or undermine design aspirations (e.g., features to promote interaction, chance encounters etc.), and further highlights the need for an evidence-based approach, that can consider the socio-technical requirements of workplaces.

The Workplace Index

This complexity emphasises the importance for an in-depth understanding of how people work, to allow designers to better respond to the demands of contemporary working arrangements as they continue to be driven by fundamental shifts.

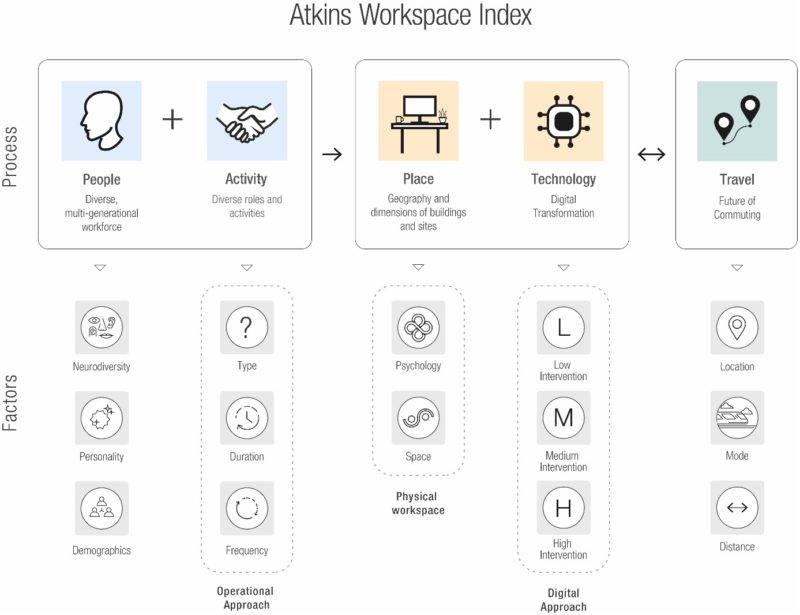

Atkins’ Workplace Index was developed in response to this challenge, to support designers in following an evidence-based approach that incorporates the understanding of employee characteristics and work preferences, the type and frequency of activities they undertake, and other factors adapted from a socio-technical perspective. The team identified common challenges during the briefing stages of workplace design projects, which led to the development of this framework following an action research approach (Zuber-Skerritt et al., 2002). This included workshops, high level reviews of literature and industry trends, engagement with existing clients who were interested in testing this methodology on their projects, and collaborations with university partners.

The Workplace Index includes five areas that can be used to identify project priorities and subsequent research to be acquired with the aim to support the development and evaluation of appropriate design solutions:

- ‘People’: Characteristics and requirements of a diverse and multi-generational workforce, the choices of which affect spatial and organisational provision requirements.

- ‘Activities’: Range of roles, tasks and focus areas within contemporary workplaces that outline an operational approach that best responds to the requirements of organisations.

- ‘Place’: Aspects of geography, and dimensions of buildings and sites, directly related to the physical workspace which highlight opportunities and challenges for design.

- ‘Technology’: Technological requirements and digital transformation.

- ‘Travel’: The future of commuting to and from work.

Within each theme are several metrics and recommendations which are mapped to different outcomes, allowing the direct and structured incorporation of findings from wider academic studies, and collaborations with academic partners into the design process. As new information is published, the Workplace Index continues to undergo iterative development as we continue to work with and alongside clients to address various challenges, ensuring that design solutions are always informed, up-to-date and in tune with current trends and contemporary requirements.

Conclusions

The Workplace Index is an ongoing project, which enables designers to address the complexities of working in a post-pandemic world and highlights the benefits of active collaboration between academia and practice. As an industry partner in this collaboration, Atkins contributed their current experience of designing in a rapidly changing sector, and had more direct and timely access to evidence from leading research from the University of Leeds to inform and evaluate subsequent design decisions. As the Workplace Index continues to develop, the impact of varied factors on different outcomes will be considered further, drawing on evidence from the University of Leeds research, on factors such as employee satisfaction and wellbeing, or social networks and social cohesion in the workplace. Moving forward, evidence-based design tools like the Atkins Workplace Index can help inform spatial configuration, technological provisions, and provide ways to better understand client requirements during early design stages. As we continue to learn more about the ways space can be adapted to suit our new ways of working, and ongoing uncertainties in the workplace sector, evidence-based design will continue to grow in relevance and importance.

Authors

Dr Matthew Davis (https://business.leeds.ac.uk/staff/291/dr-matthew-davis) is an Associate Professor in Organisational Psychology at Leeds University Business School. Matthew has worked on a range of applied research projects with corporate partners including Rolls-Royce, Marks and Spencer, Next, Atkins, Arup and British Gas. Matthew is currently leading a ESRC funded multi-disciplinary project examining office adaptations in response to COVID-19 and how office design and ways of working impact employee social networks, workflow and performance. You can find out more about the research and access podcasts, videos, infographics and more at: www.bitly.com/adaptingoffices

Dr Linhao Fang is a Researcher in Information Systems at Leeds University Business School. Linhao has a background in Information Systems, with academic interests around technology-enabled self-regulation, Design Science Research, Educational Technology, Educational Psychology, Learning Theories, Information Technology use in organisations, Digital Workplaces and Socio-Technical Systems. He has over 10 years of research experience through various multi-disciplinary projects.

Archontia Manolakelli is an ARB-chartered Architect and interdisciplinary Design Researcher at Atkins, with a master’s degree in Psychology. She has 5+ years of practice-based experience working as a designer and member of the Atkins Building Design Research and Innovation team. Her work takes place in the intersection between human experience, architectural design, digital technology, and environmental sustainability, where she utilises quantitative and mixed-method approaches from social science towards evidence-based design. Her research to date has explored personality and spatial selection in university workspaces, interpersonal distancing preferences and personal space in corporate offices, and neurodiversity requirements for post-pandemic workplaces.

- Dr Matthew Davis

- Dr Linhao Fang

- Archontia Manolakelli

References

Centre for Health Design (2022) About EBD. The Center for Health Design. [Online] [Accessed on 14 January 2022] https://www.healthdesign.org/certification-outreach/edac/about-ebd.

Davis, M. (2022) Adapting Offices for the Future of Work Stage 1 Report. Sway.office.com. [Online] [Accessed on 14 January 2022] https://sway.office.com/xvmFPc0I9RoEZXs2?ref=Link.

Ulrich, R. (1984) ‘View Through a Window May Influence Recovery from Surgery’. Science, 224(4647) pp.420-421.

Zuber-Skerritt, O. et al. (2002) ‘The concept of action research’, The Learning Organization, 9(3), pp. 125–131. doi: 10.1108/09696470210428840.